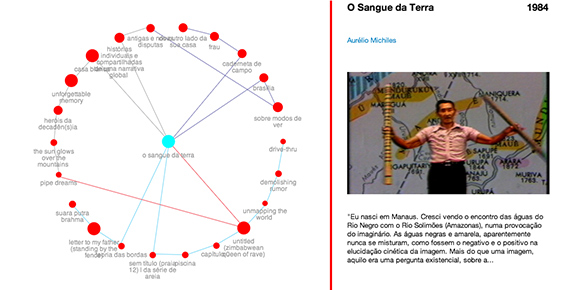

Aurélio Michiles

A significant part of the Manaus-born documentarian Aurélio Michiles’ filmography focuses on retrieving the history of the state of Amazonas, especially its indigenous peoples. Michiles’ work was honored recently, during the 5th Ethnographic Film Festival (Manaus, 2011) and by the Amazonas Academy of Letters (Manaus, 2012).

The documentary O Sangue da Terra (Earth’s Blood, 1984) is featured in Unerasable Memories and has been part of the Videobrasil Collection since its appearance in the 2nd edition of the Festival (1984). In a text about the piece, available in the exhibition book, the curator Cristiana Tejo inquires: “which issues remain repressed in Brazilian society? Who is invisible nowadays? Of all the so-called ‘minorities’ in Brazil, perhaps the most silenced one is the indigenous peoples.”

In 1979, Michiles received funding from Funarte [National Foundation for the Arts] to make a documentary about guaraná farming by the Sateré-Mawé indigenous people, who inhabit the area from the mid-Amazonas River to the border with the state of Pará. During the filming process, the director was called upon by the indigenous community to look at history on the making: under a liability contract with Petrobrás, the oil company Elf Aquitaine invaded the land of the Sataré-Mawé in 1981, cutting down trees, burning the forest and setting up oil pumps across the territory. The piece’s title, as Michiles tells PLATFORM:VB, is inspired by a statement from Tuxuaua Emílio: “How can one tamper with the underground and not tamper with those who live on the ground? Oil is the earth’s blood.”

Dico Sateré, a representative of Sateré-Mawé leadership in Manaus, plays a major role in the documentary and in the achievements of this indigenous population. Tribal chiefs were not consulted and accused FUNAI of connivance. In the face of the oil company’s repeated invasions, in breach of past agreements and indemnifications, the Sateré-Mawé rose, no longer using bows and arrows but, in their own words, using the “law of the white man.”

Having failed to find oil in the prospected areas, Elf Aquitaine left the area without removing its pumps or notifying the government of their location. Cristiana Tejo highlights the fact that “indigenous people found some of the pumps and, unaware of the radioactive contents of Cesium 137, started using them to heal wounds, kill ants and other purposes. The environmental impact was never assessed, and the tragedy was not made public by the media thanks to a military government cover-up of the issue.”

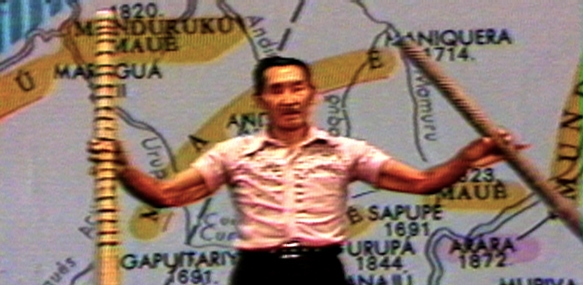

O Sangue da Terra features interspersed footage of Sateré-Mawé representatives explaining their traditions and telling history from their perspective – including their participation in Cabanagem, a revolt against the Regency Government that took place from 1835 to 1840. In the video, they talk about their customs and tools, such as the Porantim, a carved wood artifact that tells the story of the Sateré-Mawé; Pau de Chuva (rain stick), presented as a battle tool; and the Tucandeira ant glove, used in rites of passage marking the transition of boys into adult life. Michiles says O Sangue da Terra remains a “reference source to the indigenous peoples themselves” until this day.

Learn more about the artist: